October 29, 2018

Trappist Father Keating, leading figure in centering prayer, dies at 95

REGIONAL

By Catholic News Service

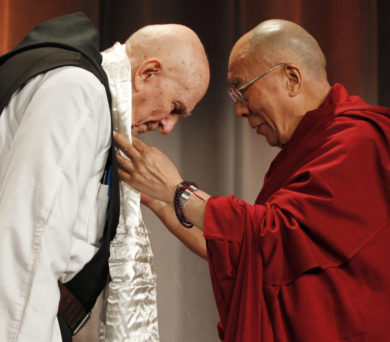

Trappist Father Thomas Keating, who was one of the principal architects and teachers of the Christian contemplative prayer movement, died at age 95 on Oct. 25 at St. Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, Mass. He is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS photo/courtesy Contemplative Outreach)

SPENCER, Mass. (CNS) — A funeral Mass will be celebrated Nov. 3 at St. Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer for Trappist Father Thomas Keating, a leading figure in the centering prayer movement that got its start in the 1970s. He died Oct. 25 at the abbey.

He had been abbot there for two decades in the 1960s and 1970s. Father Keating was 95 and, according to his nephew, Peter Jones, had been in poor health for a number of years.

Pledging to God to become a priest if he survived a serious illness he had in childhood, Joseph Parker Kirlin Keating, the son and grandson of maritime lawyers, entered the Cistercians’ Monastery Our Lady of the Valley in Valley Falls, Rhode Island, in 1944 and was ordained a priest in 1949. He took the name Thomas due to his admiration of St. Thomas Aquinas.

After the Rhode Island monastery burned down in 1950, the monks moved to the Spencer monastery. Father Keating stayed there until he was invited to help establish a new monastery in Snowmass, Colorado. He stayed until 1961, when he was elected abbot at St. Joseph’s.

He turned to centering prayer — a technique of praying silently to God without words — based on the encouragement issued by St. Paul VI during the Second Vatican Council to rediscover the contemplative tradition. Father Keating returned to Snowmass and helped found Contemplative Outreach for centering prayer practitioners in 1984, serving as its president 1985-99.

The irony for the Trappist is that, to promote centering prayer, he left the confines of the monastery to speak at conferences worldwide.

“People are feeling a deeper desire for prayer and the structure to support it,” he said in Omaha in 1990.

“Human nature has a dimension that requires silence,” Father Keating added. “The tendency had been to put people interested in the contemplative life in a convent or monastery to protect them from us — or us from them,” he joked at a conference in Omaha. “Vatican II released a lot of desire and willingness to engage in contemplative prayer and it both deserves and needs to be ministered to.”

In a homily at a 2000 Mass for the installation of Trappist Father Basil Pennington, another centering prayer proponent, at a monastery in Georgia, Father Keating reflected on the faith and suffering of Mary and Joseph. He said God’s “relentless movement” shattered the vision Mary and Joseph had for their lives, but called such movement “the path of transformation … the goal of the Christian life.”

Father Keating also was a prolific author. The Contemplative Outreach website has a page listing 28 books — what it said constituted “most of” his published works. His titles included Awakenings and Manifesting God, and he co-wrote Finding Grace at the Center: The Beginning of Centering Prayer.

Several of his books made the Catholic best-seller lists, including Journey to the Center, Invitation to Love, Open Mind, Open Heart. The latter was translated into Spanish, and Invitacian a Amar was a Spanish-language Catholic best-seller in 2005.

Trappist Father Thomas Keating receives a gift in Boston in 2012 from the Dalai Lama, exiled spiritual leader of Tibet. (CNS photo /Jessica Rinaldi, Reuters)

In a Catholic News Service review of Father Keating’s 1994 book Intimacy With God, the reviewer, Margaret O’Connell, advised readers to “drop everything” and buy the book “regardless of the effort or the effect on your budget.”

Father Keating was profiled in the 1996 PBS series “Searching for God in America,” and was the subject of a 2013 documentary made by his nephew called “Thomas Keating: A Rising Tide of Silence.”

It was from reading the priest’s Open Mind, Open Heart that a California man, Mike Kelley, decided he wanted to share centering prayer with the inmates at Folsom Prison. Paul, one of the “lifers” at Folsom, recalled the day Kelley came to talk to the men about centering prayer as “an answer to one of our prayers.” Hundreds of Folsom inmates took centering prayer classes from him.

By the time Father Keating came to California in 2000 to visit five prisons that taught centering prayer techniques, there were a dozen prisons in the program. Centering prayer is uniquely suited to effect a spiritual awakening among inmates, he said at the time. “It’s a simple way of connecting with the divine indwelling,” he noted. “It teaches them that no matter where they are, God is with them.”

He described in 2001 how one gets started in centering prayer. “The great battle in the early stages of contemplative prayer is with thoughts,” he wrote. “It is unrealistic to aim at having no thoughts.

“When we speak of developing interior silence, we are speaking of a relative degree of silence. By interior silence, we refer primarily to a state in which we do not become attached to the thoughts as they go by.”

Facebook

Facebook Youtube

Youtube