July 19, 2018

TV REVIEW: ‘Ted Williams: The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived,’ July 23, PBS

NATIONAL

By Chris Byrd, Catholic News Service

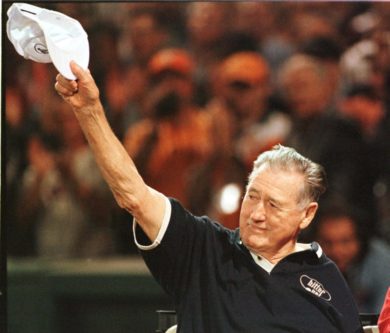

Ted Williams, a baseball legend and member of the Hall of Fame, who died in 2002, is pictured in a 1999 photo in Boston. A documentary titled “Ted Williams: The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived” premieres July 23, 9-10 p.m. EDT on PBS as part of the network’s “American Masters” franchise. (CNS photo/Brian Snyder, Reuters)

NEW YORK (CNS) — Baseball fans won’t want to miss the wonderfully revealing documentary “Ted Williams: The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived.” Part of the venerable “American Masters'” franchise, the film premieres Monday, July 23, 9-10 p.m. EDT on PBS. (Times may vary; check local listings.)

Emmy-winning actor Jon Hamm (“Mad Men”) narrates the documentary. Produced, written and directed by Nick Davis, the profile commemorates the centennial of the legendary Boston Red Sox stalwart’s birth (he died in 2002). It’s also the first “American Masters” film in its 32 years to focus on a baseball player.

Joel Goodman’s sumptuous musical score augments the rare and impressive archival film footage, captivating photographs, commentary from sports journalists, current and former players and family members as well as interviews with Williams himself. What emerges is the portrait of a complicated, flawed yet multifariously and preternaturally gifted man.

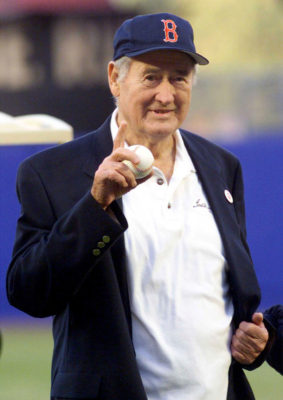

Ted Williams, a baseball legend and member of the Hall of Fame, who died in 2002, is pictured in a 1999 photo in New York. (CNS photo/Mike Segar, Reuters)

The opening sequence establishes “The Splendid Splinter” as a war hero, returning home after flying 39 missions over Korea. Future astronaut and U.S. Sen. John Glenn, with whom Marine aviator Williams often flew as a wingman, called him “one of the finest pilots” he had ever seen.

Though Williams initially sought a deferment from service in World War II, he wound up performing admirably both in that conflict and the battle for Korea. Nonetheless, “Teddy Ballgame,” according to the filmmakers, bitterly resented his military stints, which cost him five years during the peak of his career.

Already 34 when he left the service, an age at which ballplayers were considered past their prime, all Williams wanted to do was fish.

“The Kid” hadn’t swung a bat in 456 days. Yet the left-handed slugger’s first, impromptu batting practice at Fenway Park was a memorable one. During the session, Williams’ classic uppercut swing drove 13 consecutive balls over the outfield fence. And by the end, according to biographer Ben Bradlee Jr., his hands were bleeding.

Veteran sports broadcaster Bob Costas is among those who attribute Williams’ obsession with becoming “the greatest hitter who ever lived” to anger toward his parents. Each time he swung, according to this theory, Williams was, in a sense, “lashing out” at them.

The description of “The Thumper’s” childhood will intrigue viewers, and tends to lend authority to this thesis. Another biographer, John Underwood, says Williams grew up in “abject poverty” in San Diego. A lifelong foot soldier in the Salvation Army, Williams’ mother, May, became known as the “Angel of Tijuana” for her soul-saving missions across the border.

His mom’s religious fervor embarrassed the atheist Williams, and he resented her long absences from home. But he was no fan of his father, Samuel, either. According to Boston sportswriter Leigh Montville, Williams’ dad was a “ne’er-do-well and a drunk.”

That Williams was part Mexican-American will surprise many viewers. Davis frames photos of the youthful Williams to help the audience make this connection. But the Red Sox great himself tried to hide his ethnic identity.

His difficult relationship with his parents informed Williams’ relentless drive for perfection, and also was reflected in his passion for fishing. His daughter Claudia recalls her dad — a member of two fishing halls of fame — examining the stomach contents of the fish he caught to devise more enticing lures.

Mature themes of war, racism, and poverty are dealt with in “Ted Williams.” There’s a fleeting semi-nude image of model Dolores Wettach, Williams’ third wife, and commentators regularly employ strong profanity. This is a nod to the slugger’s penchant for cursing. But Bradlee, the son and namesake of the equally foul-mouthed executive editor of The Washington Post, goes too far. This problematic language suggests “Ted Williams” is suitable for adults only.

Its salty vocabulary aside, the film succeeds in portraying Williams’ contradictory nature. He wanted adulation, but refused to tip his cap to fans.

Even while denying his ethnic heritage, he successfully lobbied for the inclusion of Negro League stars in the Hall of Fame. Though he was fishing when his first daughter, Bobbi Jo, was born, Williams, without fanfare, regularly comforted pediatric cancer patients.

“Ted Williams” will naturally have the greatest appeal for baseball enthusiasts. But even viewers uninterested in the national pastime may be fascinated by this complex biography. As distinguished sports writer Roger Angell (“Late Innings”) puts it: “We’re still talking intensely and with pleasure about Ted Williams. That’s good enough.”

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

Facebook

Facebook Youtube

Youtube